|

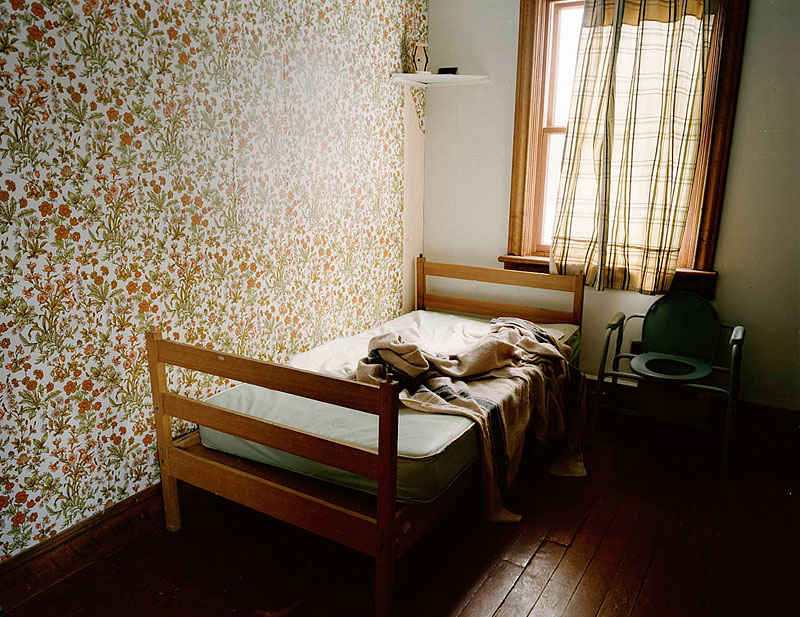

| Image credit: Jonas St. Michael Bedroom#2, 2009, C-Print, 30in x 40in |

The photographer's fascination with his subject matter is unclear. The stories told are incomplete. No one photo stands out from the rest, and as a whole set, they do not say much. They exist between the realms of different realities, not rich enough to be a dreamscape and too dewey-eyed to be documentary, and yet, there is something there.

St Michael's other series, Members Only, on the austere empty rooms of old clubs and private spaces, doesn't seem to fit into the passive romance of the Gore, Quebec series at all, but perhaps is a bridge that ties into the Projex Room exhibition, Not Another Fucking Landscape. Curated by ex-Edmontonian Anthony Easton and featuring photographic works by Amie Rangel, Marshall Watson, Ted Kerr and Zachary Ayotte, the show as a whole is speaking directly to the iconic Canadian landscape as captured in paintings that represent this country to us, as much as to the rest of the world. Attempting to strip away the sublime of the landscape by calling upon photography rather than oil paint, Easton also frames his challenge by distinguishing a west versus east mentality as much as a new versus old in what we represent and how we represent ourselves: while Rangel focuses on the clinical mechanics of modernized pig farms and Watson cheekily situates a plastic mallard duck within the watery confines of urban domesticity, Kerr and Ayotte fall very much into the category of Romantic Photographers, summoning all the awe of landscape painters from yesteryears.

Ayotte assembles his 4 x 6 photographs into a sprawling, clearly uncontained shape dominating its own wall. Carrying a similar documentary feel to St Michael in the other room (in fact, Ayotte wrote the Latitude 53 monograph for St Michael), the reality presented on the wall is filled with love for friends, lovers, light, homes, roads and a life that has often been absent from landscapes. Kerr, on the other hand, presents somewhat of an altar of absent memories. As a series of interior home photographs imbued with familiarity, yet estranged, they sit precious as decorative memories, askew in what is there and what is missing.

While this show is certainly a prairie-centric demonstration of contemporary landscape, it would have benefited from representation from across the country to show how landscape and landscape artists have changed. Just as the recent National Portrait Gallery show did wonders for how we can view a traditional format such as portraiture, this show begins to open up what we can justifiably call Canadian landscapes.

*First published in Vue Weekly

No comments:

Post a Comment