As the only dance show in last year's Fringe as a BYOV entry, Afternoon Delight had the Edmonton-based Good Women Dance Collective putting its neck out there in performing to a largely narrative-centric audience. As a simple movement piece with no dialogue and elements of slapstick physical comedy, the show got a mixed bag of reviews from audiences who found it entirely refreshing to feedback that bordered on the enraged and the confused. With perhaps the only common denominator of a stage, contemporary dance and fringe theatre have little else in common, but the risk seems to be paying off as GWDC returns to the Fringe proper this year with This Is Not A Play, a three-part dance kebab interspliced with short film works at the Catalyst Theatre.

Catching up with Ainsley Hillyard, one-third of GWDC, she notes that the title is a direct response to last year's experience of being the only dance show in a theatre festival. She says over coffee, "I remember when we were postering for the show, everyone would ask, 'What's your play about?' and we would explain that we're doing a dance show, and they would pause, and ask again, "So what's your play about?'" So we decided to just make it more clear this time around."

With three short pieces each choregraphed by a member of the collective (Hillyard, Alida Nyquist-Schultz, and Alison Towne), there are no throughlines from one piece to the next, with very different styles ranging in inspiration from Jimi Hendrix to braille to the ups and downs of social transformations.

As a collective that started in 2007 as a means to band together to create, produce, present and perform dance within Edmonton, GWDC began with the hope that it was possible to work as professional dancers in Edmonton when opportunities appeared few and far between. While Hillyard was not part of the original collective, joining after completing her Bachelors of Arts in Dance at the University of Winnipeg, she has pushed the group forward over the past year and a half with more showcases and presence, stressing the importance to see and support more dance, but also to talk and educate the community and audiences.

She continues, "We really wanted to break into the theatre scene because that community is much bigger than the dance community here. I think that in Edmonton where we have pockets of small arts communities, we should integrate and support each other. I would love to see audiences challenge themselves by having a new experience."

Recognizing that theatre in Edmonton is more traditional and linear, Hillyard believes that contemporary dance—while being more abstract—is not that far of a stretch for audiences who already enjoy the aspect of live performance.

The interesting thing to me is that the Fringe has been an enormous influence over the years in shaping the direction and expectation of theatre and live art for audiences and emerging artists alike. Proportionately as the most popular framework for most folks to go and catch a live show, often serving as the first (and last) time many Edmontonians will even see live theatre, and existing as a professional goal and model for local emerging artists, the idea and reality of the Fringe Festival has at once made live art to be something entirely accessible, but at the cost of often expecting only small shows with low production values, perpetuating a trap of sorts that has not necessarily allowed much evolution in the artistic format. With the entry of local dance into the Fringe, it's perhaps a small sign that discipline crossovers can succeed here on a mass level, and that the fringe of the Fringe Festivals such as the smaller movement arts and performance art festivals can also grow without segregation.

Already this year GWDC are no longer the sole dance artists in the lineup with local Kelsey Acton getting in on the Fringe action. As Hillyard conclues, "I see Fringe as a big party and the dance kids got invited." And here's hoping the party starts to liven up.

*First published in Vue Weekly

An archive of art writings from across the prairies. Circa 2007 - 2012. Est. by Amy Fung.

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Friday, August 13, 2010

Audio Interview with Good Women Dance Collective*

This week, Prairie Artsters speaks with Ainsley Hillyard about bringing

dance to a theatre audience. Hillyard and her Good Women Dance

Collective will be presenting "This Is Not A Play", a series of short

dance pieces and dance films as part of the Fringe this year.

For more information, visit:

www.fringetheatreadventures.ca

www.goodwomen.ca

*First aired on CJSR's Newsroom with Tiffany Brown Olsen

dance to a theatre audience. Hillyard and her Good Women Dance

Collective will be presenting "This Is Not A Play", a series of short

dance pieces and dance films as part of the Fringe this year.

For more information, visit:

www.fringetheatreadventures.ca

www.goodwomen.ca

*First aired on CJSR's Newsroom with Tiffany Brown Olsen

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Jonas St. Michael and Not Another Fucking Landscape, Latitude 53, July 30 - Sept 4, 2010*

There is some confusion between the "real" and the "imagined" when it comes to a documentary-style esthetic. I believe that confusion comes from a false conflation of "documentary" with a sense of "real," with some definite form of "truth." Documentary-based photography may not stage its scenarios, but the art of documentary is still riddled with choices, and the outcomes of those choices shape and frame a reality that is neither real nor imagined.

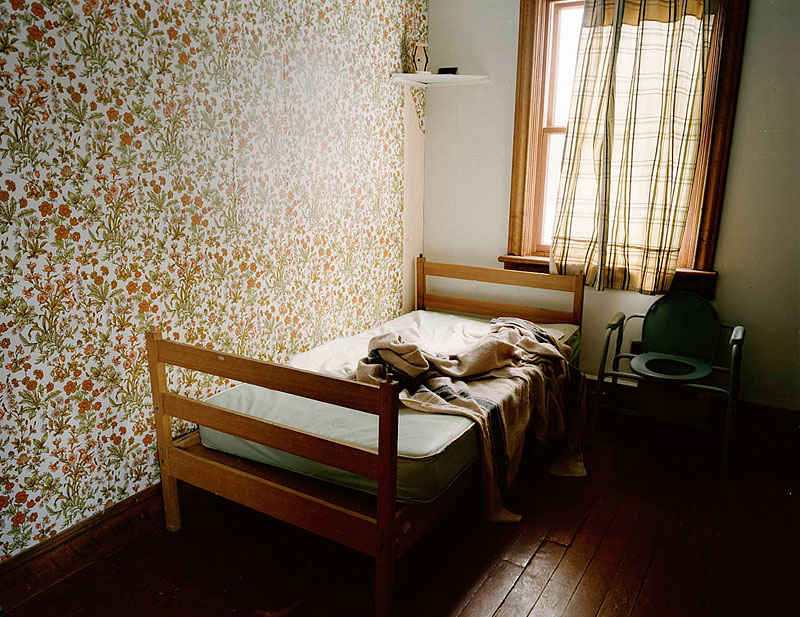

These thoughts ran through my head as I walked through Jonas St Michael's Gore, Quebec at Latitude 53. As a portrait series of Kerr's Farm, an old farm house set in wintery rural Quebec that has since been turned into a therapeutic retreat for the disabled, St Michael walks us through the old house and basks in its empty chairs, empty beds and all the ghostly cues of natural light filtering through billowing window curtains.

The photographer's fascination with his subject matter is unclear. The stories told are incomplete. No one photo stands out from the rest, and as a whole set, they do not say much. They exist between the realms of different realities, not rich enough to be a dreamscape and too dewey-eyed to be documentary, and yet, there is something there.

St Michael's other series, Members Only, on the austere empty rooms of old clubs and private spaces, doesn't seem to fit into the passive romance of the Gore, Quebec series at all, but perhaps is a bridge that ties into the Projex Room exhibition, Not Another Fucking Landscape. Curated by ex-Edmontonian Anthony Easton and featuring photographic works by Amie Rangel, Marshall Watson, Ted Kerr and Zachary Ayotte, the show as a whole is speaking directly to the iconic Canadian landscape as captured in paintings that represent this country to us, as much as to the rest of the world. Attempting to strip away the sublime of the landscape by calling upon photography rather than oil paint, Easton also frames his challenge by distinguishing a west versus east mentality as much as a new versus old in what we represent and how we represent ourselves: while Rangel focuses on the clinical mechanics of modernized pig farms and Watson cheekily situates a plastic mallard duck within the watery confines of urban domesticity, Kerr and Ayotte fall very much into the category of Romantic Photographers, summoning all the awe of landscape painters from yesteryears.

Ayotte assembles his 4 x 6 photographs into a sprawling, clearly uncontained shape dominating its own wall. Carrying a similar documentary feel to St Michael in the other room (in fact, Ayotte wrote the Latitude 53 monograph for St Michael), the reality presented on the wall is filled with love for friends, lovers, light, homes, roads and a life that has often been absent from landscapes. Kerr, on the other hand, presents somewhat of an altar of absent memories. As a series of interior home photographs imbued with familiarity, yet estranged, they sit precious as decorative memories, askew in what is there and what is missing.

While this show is certainly a prairie-centric demonstration of contemporary landscape, it would have benefited from representation from across the country to show how landscape and landscape artists have changed. Just as the recent National Portrait Gallery show did wonders for how we can view a traditional format such as portraiture, this show begins to open up what we can justifiably call Canadian landscapes.

*First published in Vue Weekly

|

| Image credit: Jonas St. Michael Bedroom#2, 2009, C-Print, 30in x 40in |

The photographer's fascination with his subject matter is unclear. The stories told are incomplete. No one photo stands out from the rest, and as a whole set, they do not say much. They exist between the realms of different realities, not rich enough to be a dreamscape and too dewey-eyed to be documentary, and yet, there is something there.

St Michael's other series, Members Only, on the austere empty rooms of old clubs and private spaces, doesn't seem to fit into the passive romance of the Gore, Quebec series at all, but perhaps is a bridge that ties into the Projex Room exhibition, Not Another Fucking Landscape. Curated by ex-Edmontonian Anthony Easton and featuring photographic works by Amie Rangel, Marshall Watson, Ted Kerr and Zachary Ayotte, the show as a whole is speaking directly to the iconic Canadian landscape as captured in paintings that represent this country to us, as much as to the rest of the world. Attempting to strip away the sublime of the landscape by calling upon photography rather than oil paint, Easton also frames his challenge by distinguishing a west versus east mentality as much as a new versus old in what we represent and how we represent ourselves: while Rangel focuses on the clinical mechanics of modernized pig farms and Watson cheekily situates a plastic mallard duck within the watery confines of urban domesticity, Kerr and Ayotte fall very much into the category of Romantic Photographers, summoning all the awe of landscape painters from yesteryears.

Ayotte assembles his 4 x 6 photographs into a sprawling, clearly uncontained shape dominating its own wall. Carrying a similar documentary feel to St Michael in the other room (in fact, Ayotte wrote the Latitude 53 monograph for St Michael), the reality presented on the wall is filled with love for friends, lovers, light, homes, roads and a life that has often been absent from landscapes. Kerr, on the other hand, presents somewhat of an altar of absent memories. As a series of interior home photographs imbued with familiarity, yet estranged, they sit precious as decorative memories, askew in what is there and what is missing.

While this show is certainly a prairie-centric demonstration of contemporary landscape, it would have benefited from representation from across the country to show how landscape and landscape artists have changed. Just as the recent National Portrait Gallery show did wonders for how we can view a traditional format such as portraiture, this show begins to open up what we can justifiably call Canadian landscapes.

*First published in Vue Weekly

Thursday, August 5, 2010

Prairie Artsters: Summer Visits*

I've written before about studio visits, most particularly in the form of detailed reports with artists whom I was lucky enough to meet on the fly. From my first visit with the great Alex Janvier to the dozens that have come since, the studio holds a mystery that engages with my critic's side, fuels my curatorial side and still enraptures the part of me that simply enjoys the simple pleasure of looking at art.

In the uncharted and seemingly brief history, the studio visit is often the undocumented exercise between an artist's works-in-progress and that of an outside eye. In other disciplines, especially performance-related mediums such as theatre or dance, this would be the equivalent of a workshop, a salon or a showcase of unfinished work for feedback and notes. Visual art has little to no equivalent of such. The artist, and if they're lucky, their production team, works often in isolation from outside eyes until the day of install. The opening is thus the unveiling, with a sizable amount of pressure attached, and I believe this is a fundamental crisis in the visual art world—that not enough process and feedback has occurred before the work gets thrown into the public eye, a public that doesn't necessary want to have to play catch up with the ongoing art historical conversation that is most gallery and museum-level art.

The more opportunities for visual artists to show their works-in-progress, the better, as communication in and around the art world can only approve. Studio critiques appear to be a regular exercise when in art school, forcing students to verbally enunciate a word or two about their work, or God forbid, defend their work to questions. One translation of that has surfaced as of late: Latitude 53 recently began showing a members' series that lasts for a few days at a time, and the one I've caught so far, by Marc Seigner, appears to be quite different from his known body of work in printmaking, and it was positive to see a space for experiments and works in progress.

Perhaps in this instant age, where anyone and everyone can self-publish their thoughts, ideas and images with hardly a filter, the concept of intellectual kneading seems out of date or simply out of fashion.

But the live exchange will never be replaced, and I prefer the face to face studio visit. Talking about art in any descriptive tone will never do the work of art any justice, as it ignores the experience of the work, but talking about an artwork with its maker is another experience in and of itself. There is always an ungauged and often illuminating conversation that will have to happen between the artist and the guest, and that to me holds the kernel for the basest raw material of any art work I have ever witnessed.

Engaging in a series of visits this summer that will continue on through the rest of August, I have sat in many a well-lit studio, basement studio, living room, spare bedroom, public cafe and kitchen table discussing the work by some of Alberta's finest as well as some of the province's newest artists. With no other purpose than to simply glance inside their working studio or portfolio, and to hear the artist speak about the work from his or her own words, the experience has always been worthwhile and memorable. Purely from a point of discovery, it's completely fascinating to view and learn the chronology of an artist's portfolio. Often knowing an artist by a particular style from a recent show or a series of work, to get a greater sense of its formation and connection from earlier works, artists, residencies and moments and memories in social and pop history, creates a richer network of ties and dissonances that are unearthed, and inform all of our stories.

*First published in Vue Weekly

In the uncharted and seemingly brief history, the studio visit is often the undocumented exercise between an artist's works-in-progress and that of an outside eye. In other disciplines, especially performance-related mediums such as theatre or dance, this would be the equivalent of a workshop, a salon or a showcase of unfinished work for feedback and notes. Visual art has little to no equivalent of such. The artist, and if they're lucky, their production team, works often in isolation from outside eyes until the day of install. The opening is thus the unveiling, with a sizable amount of pressure attached, and I believe this is a fundamental crisis in the visual art world—that not enough process and feedback has occurred before the work gets thrown into the public eye, a public that doesn't necessary want to have to play catch up with the ongoing art historical conversation that is most gallery and museum-level art.

The more opportunities for visual artists to show their works-in-progress, the better, as communication in and around the art world can only approve. Studio critiques appear to be a regular exercise when in art school, forcing students to verbally enunciate a word or two about their work, or God forbid, defend their work to questions. One translation of that has surfaced as of late: Latitude 53 recently began showing a members' series that lasts for a few days at a time, and the one I've caught so far, by Marc Seigner, appears to be quite different from his known body of work in printmaking, and it was positive to see a space for experiments and works in progress.

Perhaps in this instant age, where anyone and everyone can self-publish their thoughts, ideas and images with hardly a filter, the concept of intellectual kneading seems out of date or simply out of fashion.

But the live exchange will never be replaced, and I prefer the face to face studio visit. Talking about art in any descriptive tone will never do the work of art any justice, as it ignores the experience of the work, but talking about an artwork with its maker is another experience in and of itself. There is always an ungauged and often illuminating conversation that will have to happen between the artist and the guest, and that to me holds the kernel for the basest raw material of any art work I have ever witnessed.

Engaging in a series of visits this summer that will continue on through the rest of August, I have sat in many a well-lit studio, basement studio, living room, spare bedroom, public cafe and kitchen table discussing the work by some of Alberta's finest as well as some of the province's newest artists. With no other purpose than to simply glance inside their working studio or portfolio, and to hear the artist speak about the work from his or her own words, the experience has always been worthwhile and memorable. Purely from a point of discovery, it's completely fascinating to view and learn the chronology of an artist's portfolio. Often knowing an artist by a particular style from a recent show or a series of work, to get a greater sense of its formation and connection from earlier works, artists, residencies and moments and memories in social and pop history, creates a richer network of ties and dissonances that are unearthed, and inform all of our stories.

*First published in Vue Weekly

Sylvia Ziemann's Homeland (In)Security and Paul Bernhardt's Control, Harcourt House, Jul 29 - Aug 28, 2010*

Sitting in her home in Regina and watching a documentary on PBS about suicide bombers, Sylvia Ziemann was shocked to witness the presence of a female bomber. Portrayed as sentimental, seeking revenge for the loss of her family and her children, the story of the female suicide bomber rocked Ziemann, who recognized that it was the form as much as the content that was disturbing her.

Channeling the fear imposed on viewers by an ever-aggressive news media, Ziemann premieres Home (In)Security, her series of voyeuristic sinisterisms that date back to 2005. Included in the array of works is her initial reaction in the form of "Bomber Woman," a barbie doll figurine with Ziemann's face dressed up as a suicide bomber. The piece hangs alone, neither contextualized or politically correct, but it is the starting point for how someone far removed from international politics can begin to engage in interwoven issues and identities as filtered through a hyperbolic media.

One piece in the corner shows an elderly woman, Ziemann's mother, asleep in bed as the sky outside her window explodes with gunfire. Her mother, who grew up in the midst of the Second World War, began having nightmares of being back in Nazi Germany when the Iraq War began being televised. Another piece, "Garage," recalls news stories and childhood memories of news stories of young girls disappearing from nearby residential neighborhoods, only to resurface months or years later, having been living trapped and hidden beneath secret bunkers.

Fairy tale-like in assemblage, with direct references to folk myths such as Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel, the "beware of strangers" sentiment is turned inside out in Ziemann's worlds, and the looming fear, perpetuated by the media, of our friends and neighbors is here turned towards the mundane. Calling upon our voyeuristic intuition to peer into open windows, each of Ziemann's model houses appear like any house you would find across the prairies, with detailing down to the weathered couch on the front porch to the rubble and garbage bags strewn beneath. It is only upon our own closer inspection, our need to invade past public and into private territory, where we are satisfied with stories of kidnapping, weapons and bomb preparations, and signs of security disturbances.

Playing off the psychology of fear in collapsing the us versus them mentality of how the media portrays good and evil, the terror is here made mundane, injected into each humdrum isolated house, and calls into question our preoccupation with homeland security and personal security as more fear mongering than actual protection.

In contrast to the insecurities of control in Ziemann's main space show, Edmonton-based painter Paul Bernhardt's large-scale paintings play up the folly of control through large-scale impositions across our horizon. Taken from sketches overlooking oil derricks, airport terminals and power stations, Bernhardt finds an internal conflict playing out in three large landscapes that delve into the wretched and the beauty of these overarching mechanics and lifeblood of modern society. Building from earlier works, including his pieces currently in the Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: Timeland (at the AGA until August 28), Bernhardt's landscapes are saturated with textures bleeding out of architectural spectres. His palette distorts what one sees into an abstraction of smells and taste, conjuring sentiments of cool aqua steels and acidic orange rusts.

As a strange, yet comforting complement to each other's exhibitions, the paired viewing experience of Ziemann and Bernhardt drives home the simple fact that control and security are both decorative illusions.

*First published in Vue Weekly

Channeling the fear imposed on viewers by an ever-aggressive news media, Ziemann premieres Home (In)Security, her series of voyeuristic sinisterisms that date back to 2005. Included in the array of works is her initial reaction in the form of "Bomber Woman," a barbie doll figurine with Ziemann's face dressed up as a suicide bomber. The piece hangs alone, neither contextualized or politically correct, but it is the starting point for how someone far removed from international politics can begin to engage in interwoven issues and identities as filtered through a hyperbolic media.

|

| Detail From Sylvia Ziemann's Homeland (In)Security |

Fairy tale-like in assemblage, with direct references to folk myths such as Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel, the "beware of strangers" sentiment is turned inside out in Ziemann's worlds, and the looming fear, perpetuated by the media, of our friends and neighbors is here turned towards the mundane. Calling upon our voyeuristic intuition to peer into open windows, each of Ziemann's model houses appear like any house you would find across the prairies, with detailing down to the weathered couch on the front porch to the rubble and garbage bags strewn beneath. It is only upon our own closer inspection, our need to invade past public and into private territory, where we are satisfied with stories of kidnapping, weapons and bomb preparations, and signs of security disturbances.

Playing off the psychology of fear in collapsing the us versus them mentality of how the media portrays good and evil, the terror is here made mundane, injected into each humdrum isolated house, and calls into question our preoccupation with homeland security and personal security as more fear mongering than actual protection.

In contrast to the insecurities of control in Ziemann's main space show, Edmonton-based painter Paul Bernhardt's large-scale paintings play up the folly of control through large-scale impositions across our horizon. Taken from sketches overlooking oil derricks, airport terminals and power stations, Bernhardt finds an internal conflict playing out in three large landscapes that delve into the wretched and the beauty of these overarching mechanics and lifeblood of modern society. Building from earlier works, including his pieces currently in the Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: Timeland (at the AGA until August 28), Bernhardt's landscapes are saturated with textures bleeding out of architectural spectres. His palette distorts what one sees into an abstraction of smells and taste, conjuring sentiments of cool aqua steels and acidic orange rusts.

As a strange, yet comforting complement to each other's exhibitions, the paired viewing experience of Ziemann and Bernhardt drives home the simple fact that control and security are both decorative illusions.

*First published in Vue Weekly

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)